At the conclusion of the previous post, I stated that I would like to use this blog not only for a discussion of Malaula!, but also for future projects. Five years later, I finally have occasion to do so.

After Malaula! was published, I decided to embark upon a solo project. For quite some time I had thought that Wir Flieger: Kriegserinnerungen eines Unbekannten ("We Flyers: Wartime Reminiscences of an Unknown Airman"), by Otto Fuchs, should be translated.

Wir Flieger is an autobiographical novel in which Otto Fuchs describes his flying experiences during the First World War, initially in an artillery observation unit, and then as a fighter pilot. Though most of what is related is based on fact, the names of persons, flying unit identifications, and airfield locations have been changed. There are also some changes in the chronology of events. Other elements are purely fictional, such as dialogs.

I knew that I had to do more than simply translate Wir Flieger. A proper treatment of the work would have to involve an investigation into the true facts behind the story. I researched this to the fullest extent possible, consulting literature on the subject, delving into archives in Germany and England, and even contacting relatives of Royal Flying Corps airmen who encountered Otto Fuchs and his commander, Hans Bethge, in the air.

The end result is a book titled Flying Fox: Otto Fuchs–A German Aviator's Story, 1917-1918. The latter portion of the title has a twofold meaning. It is a story told by a German aviator in the form of an autobiographical novel, and it is also a story about that German aviator, as related in the "Introduction" and in the chapter-by-chapter commentary and epilog which comprise "Part 2" of the book.

In Part 2 many of the identities of the actual persons behind the pseudonyms are revealed, as well as the actual airfield locations (except in the latter part of Chapter 7 of the novel, all other locations are factual), and the precise dates on which the described events took place. The last section of Part 2 is an epilog describing Otto Fuchs' experiences from the time the novel concludes in April 1918 to the end of the war.

The book, published by Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., was beautifully produced, using the best quality paper for excellent photographic reproduction. There are 149 photographs, as well as 11 maps. I really like the fact that the dustjacket design has been reproduced on the glossy cover of the book itself. This cover was designed by Bob Biondi, who also asked for my input. I suggested the use of the colors blue and white to represent the Kingdom of Bavaria, where Fuchs was born. Fuchs flew in both Bavarian and Prussian units, the latter being represented by the black lettering of the subtitle combined with the white of the main title. The one Prussian unit to which Fuchs was assigned was Jagdstaffel 30. The other units he flew with were Flieger-Abteilung (A)292b, Jasta 35b, and Jasta 77b. Fuchs was also attached unofficially to Jasta 11 for two days, both of which were action-packed.

Flying Fox measures 9" x 6". Based on three other Schiffer books I have in my library, I had anticipated a larger format, i.e., 11" x 9". The advantage of the smaller size is that it is certainly more wieldy than the larger-format books. Also, the smaller size has reduced the cost of the book. Theoretically, if it is more affordable, then more people will buy it. This does serve the purpose, as stated at the end of my introduction to the work, of seeking to "bring this flyer's fascinating story the broader attention it deserves."

However, some of the maps I prepared relied on the larger format for readability, and so unfortunately a few of the map images in the book require the use of a magnifying glass, and even that is not entirely sufficient. For that reason, I am making those map images available here, allowing readers who happen to look up this blog (which is mentioned in the biographical note appearing on the rear dustjacket flap and inside the rear cover) to see the map images as they were intended to be viewed. This applies not only to their size, but also to the color in the images.

I had also really hoped that the present-day views I took of Otto Fuchs' former airfields in France would be reproduced in color. Unfortunately, they appear in black-and-white. Ian Robertson, the book designer and editor, explained to me that due to "the small quantity of color images and the size and scope of the book," they would all be done in grayscale. There were 24 color images - 5 maps and 19 photos - which I am making available here.

Maps

This image shows the location of photographs taken by Rudolf Fuchs (the brother of Otto Fuchs and his observer) on April 24, 1917, as seen on pages 212 to 215. I used a map issued by the Institut Géographique National (the layout of the roads and towns has hardly changed since WWI) and then created overlays for the areas covered by the photographs. They were all taken at a uniform height of about 2500 meters, so once I got the template right for one rectangle, I could use it for all the other photos. All I had to do was add the corresponding photo report numbers, as discussed in the book. The blue (British) and red (German) trench lines were painstakingly rendered (using original trench maps as a guide) on overlays which were then affixed to the map. This appears with a caption on page 211 of Flying Fox. A full-scale version of this map can be viewed, printed, and/or downloaded at:

Clicking on "Large 1600" or "Large 2048" above the image at that site will enlarge it yet more.

Above is the excerpt from a trench map appearing on page 213, which shows the trench systems appearing in a photograph taken by Rudolf Fuchs (see below - corresponding to 3383 on the overview map). Seeing this image in color not only helps to better distinguish between the British (blue) and German (red) trenches, but also makes the course of Layes Brook (light blue) passing around "The Lozenge" much more visible.

This is the trench map excerpt (with both British and German trenches in blue) which corresponds to the oblique aerial photo taken by Franz Hailer seen on page 216.

The photo taken by Hailer. In the accompanying caption I had mentioned the words "Tote Sau" ("Dead Sow") appearing on the lower left part of the photo which indicated a mortar emplacement. The writing is much more legible here.

The above map is seen in the middle of page 278. It shows the Roman road connecting Amiens and St. Quentin. In the middle near a bend in the road (where there is also a large dip) is the village of Foucaucourt. The airfield of Jasta 77b was situated here, on the north side of the road near the bend. The source of this image was a large (and fragile) fold-out map in John Buchan's A History of the Great War, Vol. IV , which was published in 1922. Curiously, the village of Foucaucourt was missing from the map, though the crossroads where it is located were there. It was certainly an oversight, as villages of similar size (e.g., Fay) are on the map. So I made an overlay, using the same style of lettering and little blocks indicating clusters of buildings and therewith put Foucaucourt on the map where it belonged. It's still difficult to see here, so I would refer the reader to the following link:

This image from a French trench map accompanied the above on page 278. Without the presence of color, it was difficult to distinguish between the French (red) and German (blue) trench lines. Although still rather small, the reversed "L" of the Bois d'Authuile where the Nissen huts of Jasta 77b were located is a little more visible to the east of where the road dips (as indicated by the topographical contours).

Photos

Here is the photo of the L.F.G. Roland C.II "Walfisch" seen on page 96. Otto Fuchs describes how this accident occurred near the end of Chapter 3. The serial number is visible in a larger version of the photo at the following link:

The comparison photo I took in 2010. Note that half of the roof is now missing from the barn at left.

Page 97. Houplin field.

Page 97. Houplin field, looking towards the village church at Ancoisne.

Page 205. Houplin field.

Page 102. Roucourt château.

Page 227. Roucourt field.

"Plaster of Paris gods with curly locks glow in the twilight" (page 102). I wasn't able to visit the park behind the château at Roucourt, but I was able to snap this picture through an iron fence atop a low brick wall surrounding the park. It's interesting, but the partially obscured image wasn't suitable for publication.

Page 234. "Dorf Phalempin." The village of Phalempin.

Page 234. Phalempin. Rue Jean-Baptiste Lebas.

Page 235. Phalempin field.

Page 235. Phalempin. Where the hangars arranged in an "L" once stood.

Page 236. Former bomb store.

Page 236. Where the hangar with the captured rudders on the roof once stood.

The hangar seen in the photo at the bottom of page 236 once stood here. This image is not much to look at and so I did not include it in the book.

This is the exact spot where the nice little cottage serving as a "Starthaus" (readiness hut) for Jasta 30 was located. The observation platform at right would have made for a nice stand-in, had it been moved over a bit. But, as can be seen from the aerial photo on page 235, the edge of the cottage lined up with the hedgerow seen in the background, which begins directly in front of the silver-gray car at far right. Again, this plain view of a gravel-covered parking lot didn't merit inclusion in the book.

What was once a broad open field in front of the hangars, where the aircraft took off, is a track for an equestrian club and behind it a row of trees separating off this section of the former airfield. This photo was also left out of the book.

Page 282. Former airfield west of Foucaucourt-en-Santerre.

Page 283. Former airfield near Foucaucourt, looking towards the D1029.

Page 283. Looking towards the Bois d'Authuile.

Page 283. The Bois d'Authuile in autumn hues.

Page 284. Bois d'Authuile.

Page 284. The one remaining piece of one of the Nissen huts used by Jasta 77b.

Page 284. Close-up of the section of corrugated sheet metal from a Nissen hut.

This is an image I should have liked to have included in Flying Fox, but unfortunately it didn't meet the publisher's resolution standards. It was sent to me by Greg VanWyngarden, who had received it from Colin Huston. Greg said that the photo should be credited to the Royal Aero Club. This pilot is Lt. Charles H. Harriman, who flew a Sopwith Camel in 43 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps and was shot down by Fuchs on October 29, 1917 for his third victory. This incident is described on pp. 147-149 of the novel and pp. 256-257 in the commentary.

Original photos from the albums of Otto Fuchs

In April and May of 2013 original photos from the personal albums of Otto Fuchs were sold individually in online auctions. Ideally, the intact albums should have found a home in an archive such as the Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv in Munich. However, these valuable images are now in an unknown number of personal collections, including my own. I purchased 12 of the photos with the thought that, although it is unfortunately too late for their inclusion in Flying Fox, I could at least share them with the public in this blog. These are reproduced below (click on the images for an enlarged view).

This view of Phalempin airfield was taken by a reconnaissance crew on July 3, 1917, looking towards the northwest. Beyond the train tracks, which run from left to right in this picture, one can see the airfield with a line-up of Albatros fighters. The general area around the line-up is presently occupied by a track used for equestrian events and a gravel-covered parking area, as seen in the color photos above. Beyond the horse track is now a row of trees, dividing up the former airfield, which also runs behind a line of houses. There are two fields beyond enclosed by lines of trees and then finally a broad cultivated field.

A close-up from the previous photo showing the line-up of seven Albatros fighters to better advantage. There are three aircraft hangars, the two on the right forming an "L." The middle hangar is the one with the captured British rudders on the roof serving as windvanes (see pages 129 and 247 of Flying Fox). The white stripes on the rudders are visible upon close inspection, giving the impression of being white poles, while the blue and red tend to blend in with the gray background of the field. The Nieuport rudder atop the "Starthaus" with the light roof at right can also be seen when the image is enlarged.

Another close-up, showing the house in the Rue Jean-Baptiste Lebas, which is seen in the present-day photo above. At the bottom of the photo is the Rue du Plouick (with horsedrawn vehicles) which tees into this street. Note the gap in the hedge beyond, which still exists.

A final close-up. The light stretch of bare soil ending in a large dirt mound is, I believe, an area used for testing the alignment of the aircraft's machine-guns.

This photo appears on page 235 of Flying Fox. It came from the collection of the late Alex Imrie and was sent to me by the late Mike O'Connor. The photo shows a more close-up view of Phalempin airfield, as viewed from the opposite direction to the above photo.

Otto Fuchs' quarters, probably in a private house in Phalempin. Hans Bethge had noted in an evaluation of Otto Fuchs that he was well-read. Unfortunately, none of the titles of the two dozen or so books visible in this photo is legible, even in extreme magnification.

Otto Fuchs in front of an Albatros D.III. Exact date and location are unknown. According to Bruno Schmäling, this aircraft was painted green. This led Fuchs to remark: "It looks like a big grasshopper." (Page 120)

An Albatros fighter in flight, purportedly being flown by Otto Fuchs.

Here is a more full-length view of the Bristol F.2B which Fuchs shot down on June 21, 1917 for his first victory. There is a photo of this aircraft on page 138 of Flying Fox which provides a better view of the engine.

Captured British Nissen huts used by Jagdstaffel 77b. I believe this photo was taken at Foucaucourt.

As above. The identities of the pilots are unknown to me.

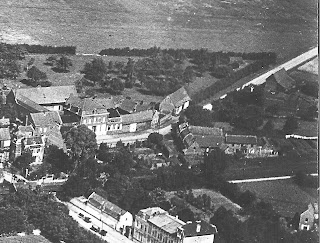

Otto Fuchs' hometown of Frankenthal in what was then a part of the Kingdom of Bavaria, but is now located in the Rhineland-Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz). I have seen other aerial photos of Frankenthal taken by Otto Fuchs in another online auction, with captions indicating they were taken on January 5, 1917. I would assume this photo was also taken around that time.

This is an aerial view of the flying school at Germersheim (Fliegerschule 7). In July 1918 Fuchs tried to transfer there from Fliegerschule 4 at Lager-Lechfeld. The reason is unknown, though one might suspect he had a friend posted there. The request was denied, as there was no suitable replacement for him as flight director at that time. "Vor den Hallen" means "In front of the hangars."

Otto Fuchs in the cockpit of a Fokker D.VI.

Otto Fuchs making a low-level bank in his Fokker D.VII after returning to Jagdstaffel 77b in October 1918. Jagdstaffel 77b was located at Marville from mid-September 1918 until the end of the war. It seems reasonable to assume that is where this photo was taken.

Otto Fuchs flying his Fokker D.VII. This photo appears on page 306 of Flying Fox, but this image is of much better quality than the print available to me at that time. One can discern the Staffel marking, a blue tail, which in this case begins at the forward edge of the national insignia and extends rearwards. This unit's markings also included blue noses.

Errata

Errors made by the editor

The editor, Ian Robertson, made some last minute changes to the text without telling me - all of them erroneous. I only discovered them when I received my advance copy of Flying Fox. The following is a list of those errors, and a couple of the editor's misplaced commas which I failed to notice when I reviewed the layout file.

Page 11: "For your war still has an element of romance."

Comment: I had written: "For you war still has an element of romance." This is a direct quote I had taken from Falcons of France, by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall (page 180 of the 1945 reprint). I have verified that the quote was correctly transcribed in the manuscript I submitted to Schiffer, so I am left to assume the editor changed it. I am puzzled as to why he would do that.

Page 15: "Victor M. Yeates . . . was invalidated out of the service with 'Flying Sickness D,' or nervous exhaustion."

Comment: I had written: "Victor M. Yeates . . . was invalided out of the service . . ." Apparently the editor was unfamiliar with the expression "to be invalided out." If he had consulted, for instance, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, he would have seen that one of the definitions of "invalid" is a verb meaning "To release or exempt from duty because of ill health." I know this was not a computer spell-checking program error, as I used the same verb on page 288, where I wrote, "Roulstone and Venmore were subsequently invalided back to England" and "invalided" remained unchanged.

Page 24: "He noted the fact that a man that had been a fighter pilot did not necessarily mean he was a cold-blooded killer."

Comment: I had written: "He noted the fact that a man had been a fighter pilot did not necessarily mean he was a cold-blooded killer." I double-checked the manuscript I submitted to Schiffer and verified that it was correct. So it was the editor who added in the second "that," which confuses the syntax and alters the meaning.

Page 44: ". . . the guzzling carburator."

Comment: A check of the manuscript reveals I had written "carburetor," which is the correct spelling. The word "carburetor" appears with the correct spelling on two other pages, 106 and 188.

Page 103: In the caption, "suddenly yielded" should be "suddenly yields".

Page 129: Caption. There should be no comma after "4887." This was present in the layout pdf file I reviewed, so I should have caught it.

Page 154: "After two uncontrolled somersaults he pulls, out and even before I can intervene he is sitting on the other's neck."

Comment: There should be no comma after "pulls."

Page 179: "I climb into the car and drive, as I am down into the small town . . ."

Comment: There should be no comma after "drive." The inserted comma changes the word "as" from an adverb to a subordinating conjunction meaning "because." This completely alters the meaning of the sentence. Again, this was in the layout file, but I missed it.

Page 206: "In some instances, but clearly not all, this is an indication that pilots and observers regularly flew with one another."

Comment: I had written: "In some instances, but clearly not all, this is an indication of which pilots and observers regularly flew with one another." It is an obvious fact that pilots and observers would form "teams" which regularly flew together. Familiarity among the crews would generally increase their efficiency. That a particular pilot would fly regularly with a particular observer is made abundantly clear in the very first chapter of the novel. This is the notion behind the German term "Fliegerehe," or "flyers' marriage," mentioned in the novel and further explained in an annotation (Endnote 48).

I had first provided the names of all known pilots and observers in the artillery observation unit (Flieger-Abteilung (A)292b) in two separate lists. Later I listed which crews had flown together on particular dates, as indicated by a collection of photo reports from that unit which I discovered at the Bavarian Main State Archive in Munich. The whole point of my original sentence was that the separate lists of pilots and observers provided no indication of who regularly flew with whom, but the photo report information perhaps provided an indication of this.

Page 210: "The blue and red lines represent the British and German lines, respectively. The two irregular lines running from the lower left corner to the upper right portion of the image represent the British (top) and German trench lines."

Comment: There is an obvious oversight in this caption accompanying the map. The first sentence was part of my original caption, written when I was anticipating the image appearing in color. The second sentence was a necessary rewrite after I was informed that there would be no color images in the book. I had indicated that the first sentence needed to be stricken.

Pages 225-7: "Wilhelm downed two enemy aircraft himself before being severely wounded in combat on May 24, 1917, and was put out of action for the rest of the war."

Comment: I had written "Wilhelm downed two enemy aircraft himself before being severely wounded in combat on May 24, 1917 and put out of action for the rest of the war." The editor failed to recognize the implied use of the word "being" in the second clause. The meaning of my original sentence was "Wilhelm downed two enemy aircraft himself before being severely wounded in combat on May 24, 1917 and [(therewith) being] put out of action for the rest of the war." The editor's change alters the meaning to: "Wilhelm downed two enemy aircraft himself before being severely wounded in combat on May 24, 1917 and [Wilhelm] was put out of action for the rest of the war." The causal connection to Wilhelm Allmenröder being put out of action is clear enough in any case, but as a result of the change made by the editor the causal connection was changed from an explicit one into an implicit one. The resulting sentence is much weaker.

Page 234: "This is illustrated for instance in the opening pages of American ace Eddie Rickenbacker's memoir Fighting the Flying Circus, which describes his and Douglas Campbell's first flight over the lines . . ."

Comment: I had written "describe." The antecedent to the relative pronoun "which" is "the opening pages of Eddie Rickenbacker's memoir," not "Eddie Rickenbacker's memoir," so the verb conjugation in the relative clause should reflect the plural form.

Page 252: "This time, though 'Patten' has once more taken his leave upon encountering enemy fighters, and Otto is actually angered by the manner in which he obtained his second victory."

Comment: My original sentence was: "This time, though 'Patten' has once more taken his leave upon encountering enemy fighters, Otto is actually angered by the manner in which he obtained his second victory." The editor failed to recognize that the clause introduced by the subordinating conjunction "though" is a dependent clause. The main idea is that the narrator is angry about how he obtained his second victory. The fact that "Patten" took off once again is a subsidiary idea. However, the editor treated both as independent clauses, inserting the coordinating conjunction "and" between them while still leaving the subordinating conjunction in place, which changes the meaning and disrupts the coherency of the sentence.

Page 272: "Still, the next day Fuchs states . . ."

Comment: There should be no comma after "still." I had written: "Still the next day, Fuchs states . . ." The phrase "still the next day" is a syntactic unit expressing a point in time, the word "still" being a temporal adverb meaning "up to or at the time indicated." Putting a comma after "still" changes it into an adverb meaning "nonetheless." This was also in the layout file, but I missed it.

Page 276: "where it met the French 6th Armée . . ."

Comment: This should be "6me Armée," which, written out in French, is "Sixième Armée." This is the form I used elsewhere throughout the text. I caught this mistake in the layout file and had indicated to the editor that it needed to be changed back.

Errors made by the translator/commentator

I too made my share of mistakes. The first error occurs in the table of contents, where its says, "Appendix 2: The Last Conversation." That was my original title for the appendix. Later I changed it to "Appendix 2: A Lost Chapter" - only I initially forgot to go back and change the title on the "Contents" page. I did discover this mistake later and informed the editor, but it was not corrected.

Page 14: "Spring's" should be "Springs'"

Page 27: There is a typographical error, where a block quote is partly contained in quotation marks. I think I failed to erase them when converting a straight quote to the block quote.

Page 57: The photo credit for the aerial view of the Houplin airfield should be the University of Texas at Dallas, not the Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv.

Page 66: A translation error. Speaking of a layer of clouds, Fuchs wrote, "They lie quite flat above me . . ." ("Sie liegen ganz flach über mir . . ."). I wrote, "They lay quite flat above me . . ." Most of the narrative is in the present tense, so I should have caught that one.

Page 68: Here is to be found the only grammatical error for which I am responsible. At this point in the translation I used an adjective instead of an adverb. The phrase "shouting loud as I can" should be "shouting loudly as I can."

Page 110: "Scholz's" comment, "I am just a glorified nursemaid," should have the word "anyway" added at the end.

Page 112: A translation error. "Would they take you?" should be "Would he take you?" I was thrown off by the article (here used as a pronoun) die, which refers to feminine or plural antecedents. Since Fuchs was talking about Karl Allmenröder, I disregarded the choice of a feminine antecedent and interpreted it as a plural, referring to the members of Jasta 11. If I had paid closer attention to verb agreement, I would have noticed that the form was singular and that the antecedent must therefore be "die Kanone," i.e., "the ace." I only noticed this while recently revisiting the passage.

Page 116 : I left the first "t" out of "Wytschaete." Consequently, this page number is missing in the place index after the entry for this town.

Page 127: A typographical error, where I wrote "green houses" instead of "greenhouses." Elsewhere in the text I did not separate the two parts of this compound noun. The same applies to "battle field," instead of "battlefield," on page 347.

Page 156: The only other translation error of which I am aware. I wrote "wonderful slippers" instead of "wonderful little slippers" ("wunderschöne Pantöffelchen"). I did not fail to recognize the diminutive suffix (and umlaut), I just neglected to include the word "little." I found this mistake later and penned in a correction in red ink and sent it to the editor. Perhaps I didn't circle the whole thing in red, and so it was left uncorrected.

Page 176: There is a semi-colon which should be a colon, namely in "Then this; . . ."

Page 195: Regarding Ernst Schlemmer, I wrote: "It was actually not until after the war - on August 22, 1919 - that he was promoted to Hauptmann." That statement was based on the following entry on p. 587 of Harald Potempa's Die Königlich-Bayerische Fliegertruppe 1914-1918 for Schlemmer: "9. Juli 1915 Oberleutnant, 22. Aug. 1919 zum überz. Hauptmann bef." However, I have now read in another source that he was promoted to Hauptmann near the end of the war, on October 18, 1918.

Page 205: I listed four types of aircraft flown by Flieger Abteilung (A)292b. I should have mentioned a fifth, an Albatros C.V, as seen in the photo line-up and as mentioned in the caption.

Page 207: This is more of an addition than an error. In discussing Rudolf Fuchs' failure to reel in the wireless aerial, I had stated: "Such an oversight was probably not uncommon. One British account states how a returning 'art-obs' plane interrupted an out-of-doors card game, in that the lead weight of its still-extended aerial smashed into the table right in front of the astonished players, flinging it over but fortunately harming no one." I had wanted to include more specific information regarding the source of that account, but I couldn't remember where I had read it. In December 2014 I was re-reading the classic memoir Sagittarius Rising, by Cecil Lewis, and found it there. It's on page 140 of the 1963 Stackpole/Giniger edition. There Lewis describes an incident which occurred when he was a member of 3 Squadron, RFC. It had been quite a number of years since I read the book and I did get one detail wrong. The extended aerial had not upset a card game at the airfield, but rather someone's tea.

Page 221: There is a mistake in the caption. Hans-Joachim Buddecke is sitting center right in the back row, not the front row. That is, he is sitting directly in front of the door on the right side.

Page 237: I identified "Scholz" as Eduard Illig. In fact, he represents Douglas Schnorr. I recently received this information from Bruno Schmäling, who wrote that, like "Scholz," Schnorr had lost a leg in an airplane crash. He added that Schnorr's mother was from England, which would account for the Jasta 30 adjutant's affectation for strewing bits of English into his conversation. The name "Douglas" also provides a clue in this regard, though I did not pay any serious attention to it.

I had in fact initially suggested that "Scholz" could be Schnorr, referring to the photo which appears on page 247. I pointed out that his left leg seemed to be cocked at an odd angle, perhaps indicating that it was a prosthesis. It did seem like flimsy evidence, though.

When I then examined the personnel file of Jasta 77b adjutant Eduard Illig and discovered that he had a lame left leg due to an injury he suffered as an infant, I thought that it couldn't be a coincidence and that Fuchs simply changed a lame leg into a wooden leg. As it turns out, it was just a coincidence.

In the final analysis, though, considering that the "Scholz" character is present during both the Jasta 30 and Jasta 77b portions of the narrative (both of which units are hidden behind the designation "Jasta 136"), he might well represent both actual individuals, who shared not only a similar malady, but also similar dispositions.

Page 265: While translating an evaluation of Fuchs written by Bethge, I unwittingly inserted typical wording I had read in a number of other similar evaluations. The phrase "he was a quite popular and respected member of his circle of comrades" should read "he was a quite popular and respected comrade."

Page 271: A statement I made here is lacking in logical precision. I wrote, "After passing through this deadly gauntlet of hot, hissing lead, Fuchs sets his Albatros down on the soft 'moor-like' soil." Technically speaking, standard machine-gun ammunition actually consisted of a jacket made from coppered sheet steel encasing a lead core. More importantly, the phrase "Fuchs sets his Albatros down" implies that he had control of his aircraft when he came down in no man's land. He did not. His controls had been damaged and he was forced to sit helplessly as the Albatros glided to a crash-landing.

Page 276: "The actual identities of these newcomers remains uncertain." That should of course be "remain," reflecting the plural subject.

Page 287: Caption. The portrait of William C. Venmore is dated May 1919. So it was not taken some time after 1922.

Pages 288-289: "Venmore underwent pilot training in 1922, receiving authority to wear wings on December 22nd of that year." James Venmore has recently informed me that his grandfather obtained his wings in October 1918. My mistaken impression regarding the date Venmore completed his pilot's training is based on the following: I had received an outline of William C. Venmore's flying career from his grandson. The June 1, 1918 entry reads "Reading Unit for Instruction in Aviation," but did not specify pilot's training. The September 19, 1922 entry, quoted from the London Gazette lists William C. Venmore as one of the "Pilot Officers on probation." "Probationary" flight officer was a common term for student pilots. The August 2, 1922 entry states: "Fit for Flying Duties as Pilot may have difficulty landing but has flown before and obtained wing." I figured that the singular "wing" referred to his observer's single-winged "O" and that his difficulties in landing were due to the fact that he was still learning to fly. The December 22, 1922 entry reads: "Authority to wear wings." I assumed that that date indicated his first award of his pilot's wings. James Venmore explained, "The London Gazette refers to him obtaining his wings in 1922 which is when he joined the RAF after the U/List (or whatever he did between 1919 and 1922)."

Page 288: Caption. "Postwar photo of William C. Venmore in a Sopwith Camel at a training field in England." James Venmore has just written me (November 28, 2012): "The photo on page 287 was taken in September/October 1918. (Only recently discovered this detail from a family album.)" This photo had confused me, as Sopwith Camels were no longer being used for training in 1922. I thought perhaps Venmore had just hopped into the cockpit for the sake of the photo sometime shortly after the war. That's why I wrote: "Postwar photo of William C. Venmore in a Sopwith Camel at a training field in England."

Page 292: "Flugzeugwerke" shouldn't be italicized. I wrote German words in italics, except where the names of companies were involved, as was the case here.

Page 293: I should have added "[sic]" as follows in the Stewart Taylor quote: " . . . He was soon to follow it—another breech [sic] of air combat rules . . ."

Page 326: Some readers might wonder why there is no question mark at the end of the sentence: "Or am I so dense." There is no question mark in Otto Fuchs' original manuscript, so I left it that way.

In the "Endnotes" section I refer three times to the annotations as "footnotes," namely in Endnotes 28, 65, and 96. The explanation for this is that my annotations were initially in the form of footnotes, but the publisher preferred the use of endnotes, and so I moved all the annotations to the back of the book in an "Endnotes" section. While doing so I failed to change the term "footnote" to "endnote" in those three annotations.

Page 365: In the "References" section under "Books," the title of the 1921 work by Douglas W. Johnson should be Battlefields of the World War, not Battlefields of the First World War. At the time of its publication, there had of course only been one world war. I included Reinhard Kastner's Bayerische Flieger im Hochgebirge under "Books" in the "References" section. It more properly belongs under "Monographs" on page 366.

Page 367: Under the list of source documents from the British National Archive 1/1219/204/5/2634 should be 1/1223/204/5/2634.

Page 370: In the name index, the page number 206 should also be listed after Leutnant Heinrich Simon.

Miscellaneous errors

There were also a couple errors which may have been program glitches. On page 17 a parenthesis appears which was not in the layout file, namely in: "Tom's conclusion is that '(he wasn't fit for the job . . ." On page 41, after the announcement by "Amsel," there should be a new indented paragraph beginning, "We frown as we look at one another . . ." This was probably due to a programming glitch.

Final comment

While preparing Flying Fox, I had told some colleagues, "This has to be done right!" Otto Fuchs' autobiographical novel deserved the best possible treatment. I wanted the end result of my efforts to be as perfect as possible, and so the above-mentioned flaws are somewhat painful to me. However, objectively speaking, they are minor blemishes which do not detract greatly from the overall value of the work.